In the palm oil sector, a pivotal theme is assessing, and protecting, areas designated as being of High Conservation Value (HCV). These can be defined as “an area designated on the basis of…biological, ecological, social or cultural values considered outstandingly significant at the national, regional or global level” (UNEP). Conducting assessments to determine prevalence and degree of such values is an essential part of the management and protection of areas of high conservation value in the sustainable palm oil sector, and one that is taken rigorously and comprehensively.

At our Sierra Organic Palm Ltd. (SOPL) estate, which is an existing plantation landscape, participatory mapping is one of the techniques that we apply within our own operations that was also used during the HCV assessment procedure to determine these values. Whilst the ecological value of say forests, rivers, or grasslands is fairly well discussed, factors that are often less explored are those that concern the importance of HCV areas within the social context, and how these might be mapped and preserved.

For this particular HCV assessment the reputable organisation HCV Africa was contracted to conduct the HCV study. HCV Africa has a wealth of experience and expertise that enable them to carry out a rigorous and comprehensive assessment. The HCV African team has the experience and technical knowledge to identify the HCV’s relating to their respective specialist fields.

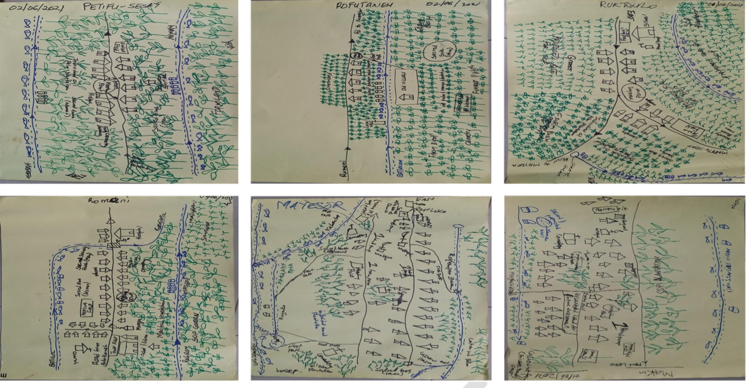

Above image is from the participatory mapping procedure in the Gbonkohmakent community of the Maconteh chiefdom during the HCV field assessment conducted by HCV Africa (June 2021).

Local environments have intrinsic values – such as through the prevalence of biodiversity, or old-growth forests that act as important carbon sinks – but these ecosystems also have a relationship with local communities by providing natural resources such as food, drinking water or firewood, and ecosystem services such as flood protection, or connections of a spiritual nature, such as traditional beliefs. Social HCVs have equal importance for protection and conservation as physically present HCV values. Therefore, when mapping any new or existing agricultural landscapes, it is essential to first determine a community’s interactions with the local environment in question.

Establishing and demarcating social and environmental HCVs must always be done with the guidance of local communities who may have exclusive and intricate knowledge of their environment – the process of which is called participatory mapping. “Participatory mapping is a general term used to define a set of approaches and techniques that combines the tools of modern cartography with participatory methods to record and represent the spatial knowledge of local communities” (Mapping For Rights).

Above image is from the participatory mapping procedure in the Mayoesor community in the Bureh chiefdom during the HCV field assessment conducted by HCV Africa (June 2021).

Participatory mapping is, therefore, a way to gain a unique and representative insight into the local environment and its layers of social interaction. In addition, and just as significantly, it is also a means of inviting communities to be a part of the HCV assessment process.

Depending on the location, context and the tools available, participatory mapping can be highly detailed, with technical tools such as GIS (Geographical Information Systems), or merely a piece of paper with landmarks and areas sketched out. Maps can always be rendered into greater detail at a later stage – the most important aspect is that communities participate in the process from the very beginning and that they understand what is being shown to them and feel confident in what they are demonstrating to the mapping team; the mapping team always includes community members to ensure collective collaboration during the mapping process.

Our SOPL estate is located in the Port Loko district – about 70km north-east of Freetown – with the HCV assessment area covering 19 communities across 119km2. Our most recent mapping exercises took place in the Bureh, Kasseh and Maconteh chiefdoms. Below are some of the maps constructed with the collaboration of the communities, company and the assessment team.

There are of course difficulties and limitations that come with this exercise – one being that it is not always easy to recreate physical elements of a 3-D reality onto a 2-D representation or visualise surroundings that you have only lived within from a birds-eye perspective; especially if those communicating the maps are not used to working with western style maps. Participatory maps can also be quite subjective, and quite far from the accurate geographical representation of the land. However, it is important to have a physical reference point to return to – for both the assessment team and the communities themselves – and visual communication is often preferable to written communication in instances where literacy is limited.

With the availability of modern satellite imagery, gaining a detailed accurate image on the ground is not what is important at the first stage (the physical gaps can easily be filled in); but rather a representation of social relationships with the land and knowing that local livelihoods and customs will not be adversely impacted.

The team can then go away and draw highly detail maps rendered from the participatory maps and the tour of the environment they received from the communities on the ground. And the consultation doesn’t stop there; communities continue to be engaged in the process during all of the company's operations. The dialogue always remains open.

Written by Jonathon Hunt